How can product managers leverage their organization’s design resources to work more strategically toward a successful product? Pragmatic Institute Design Practice Co-Director Jim Dibble and Product Instructor Amy Graham addressed the question in a January 12th Product Chat hosted by VP of Marketing and Product Strategy Rebecca Kalogeris. Below, read the webinar’s most important takeaways ― from partnering on user research to applying personas in different ways.

Sources of Friction Between Product and Design Teams

Tension, misunderstanding, and a lack of clarity around each other’s roles are familiar issues to product managers and designers. These roadblocks to collaboration make it difficult to create a coherent, cohesive product that truly fits users’ needs.

“I experienced that early in my career,” Dibble says in the webinar, “working with a product manager who was having conversations with sales and buyers while our small design team was having conversations with users. That led to a lot of churn because there was a lack of shared context for how we were going to make decisions about the product based on different perspectives we were hearing.”

Graham said she’s experienced the issue of duplicating efforts: “We end up working harder, not smarter. We don’t leverage the value that each of the two parties can bring to the table.”

The two experts shared a few oft-heard misconceptions about designers…

- You can slide designers in late into the product development process to “make it pretty” and “make it usable.”

- UX research only involves observing how users interact with a product.

…and designers’ questions about product managers.

- Are they product managers or project managers?

- How do they perform research?

Common Org Structures for Design Resources and How to Respond

If you’re a product manager looking to better leverage your company’s design function, be aware of two issues at play. On a corporate level, where does product management and design fall on the organizational chart? And on a project level, what is the resourcing model for designers?

Corporate level:

If you’re a VP or director of product, this is a concern for you. Sometimes design reports to product, sometimes it stands on its own, and sometimes it reports to engineering or marketing. As a product leader, you should build an alliance with the head of design, who can be your trusted partner in maintaining an outside-in approach.

Project level:

If you’re an individual product manager, how design is resourced on your project will tee up how you might collaborate.

In the research for Pragmatic Institute’s new course for product managers, Design, “We saw two main ways in which design is structured within the organization,” Dibble says.

- Embedded Model: Design resources are embedded within product teams. If you’re a product manager who’s leading a product or a portion of a product, you have a dedicated designer or set of designers.

- Agency Model: There is a centralized pool of designers, which you can draw from if you make the case that your particular project needs these resources. It’s as if you have an internal design agency.

There are different needs for product managers in each type of set-up.

If you have an embedded model …

Work on establishing a strong partnership with your designer. You could lean on them to help with user research, persona creation, product concept testing, product storytelling, etc. And they can see you as a partner in ideation, solution visioning, etc. Discuss who will lead and who will participate at different stages.

If you have an agency model …

Chances are you have access to a designer for a limited amount of time and that you might get a different designer each time you request one. That’s a challenge, because you’ll have to explain your product context each time. Be crisp when sharing the context designers need to do great work (who they’re designing for, what their goals are, how they currently approach the market problem, how you want the users to feel).

Making the Case for Design Resources

Organizations tend to be understaffed in design, and some don’t invest in it at all. What do you do if you don’t have access to any design resources?

Graham says she hit three main points when she was a product manager asking for a design resource:

- Provide visibility and transparency into bandwidth issues: “I can’t be everything to everyone.”

- Share challenges around skill set: “I’m not a designer…If you want me doing design just be aware I’m ‘practicing my flair.’”

- Demonstrate how critical it is to have a separation of duties.

“I also started to gather data,” she says. “I looked at our support tickets, our win/loss data, any sort of input that would speak to usability, adoption, complaints that a product is not intuitive, or if somebody used our mobile app one time and never came back. I pulled that data together and used it to build a business case to get design resources either contracted as a consultant or get them in-house.”

Dibble explains how, without a dedicated design resource, a product team is putting quality and customer satisfaction at risk. “Engineers will often talk about ‘technical debt,’ these things they need to fix in the infrastructure but haven’t had time to because they’re turning the crank so quickly. If you don’t have a designer, you’re building up ‘design debt’ ― your product is becoming more and more inconsistent visually and in the way it works. It ends up looking like a Frankenstein collection of features because you didn’t have a designer. So, if you don’t spend those resources now to get it right you’re going to have to invest them later to correct your product.”

You can also focus on business outcomes you want to achieve when advocating for resources. For example, designers have techniques for both innovating and gathering user feedback on ideas and work in progress. So, if your organization prioritizes product innovation, or wants to mitigate the risk of spending resources on developing products that aren’t embraced by users, design is a great investment.

Dibble suggests doing an analysis of what capabilities you need (see the Design Practice Identification Guide in our “Exploring Design” ebook) before hiring new designers so you make sure to apply the right skill set to your project.

Collaborating on Key Activities

While product and design might have developed different tools and mindsets over time, Pragmatic Institute sees these as complementary practices.

The Pragmatic Framework lays out the key activities required to create and market products that people want to buy. Depending on their backgrounds and capabilities, designers can serve as partners in any number of key activities.

Dibble and Graham advise product managers to learn how design capabilities overlay the Framework to pinpoint where design can add value (see Design and the Pragmatic Framework in our “Exploring Design” ebook).

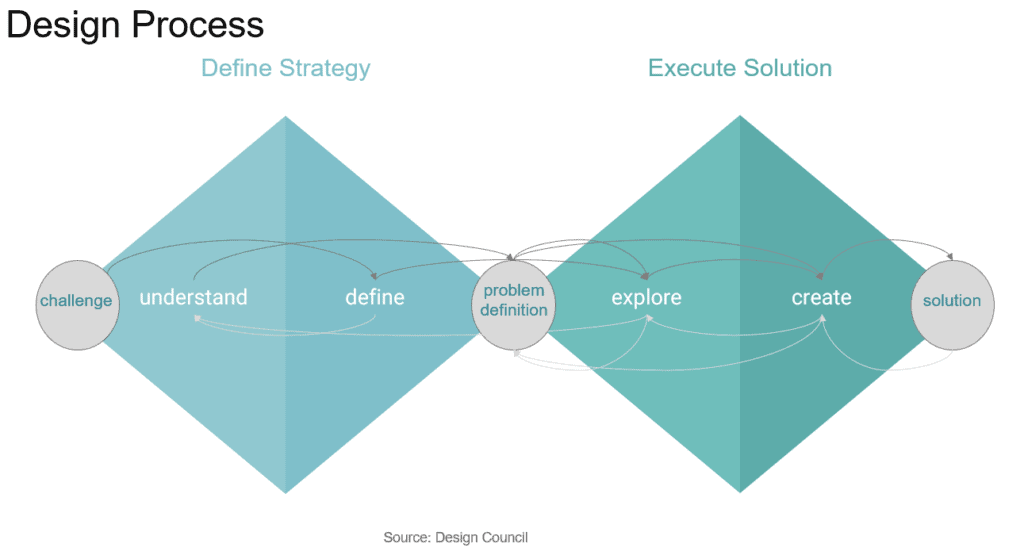

Designers see their process as two-phased (see graphic from the Design Council below):

- Understanding the problem and the context around it.

- Toying with potential solutions and then deciding how to move forward.

This means there are opportunities to leverage design skills throughout the process, not just when you’re defining the solution.

Dibble highlights the potential for friction, because designers want to frame and reframe the problem, “and that can feel itchy to product managers.” However, “there’s a real opportunity here as long as you’re aware that designers often want to participate in research and defining the problem, and at least understand how that problem affects the persona.”

The Value of Personas and Where to Apply Them

Personas are archetypes of target users that enable you to understand what needs and goals your product should support. They can be leveraged throughout the product life cycle in different ways, such as ideating with them, evaluating solutions against them, and framing feedback in persona terms.

“It is dangerous to build to a faceless user,” Graham says. Without personas, you end up designing for yourself, and you don’t know what features you have to have and what features you could potentially leave out. Personas provide much-needed context for cross-functional teams. “I used to share personas with product management, my engineers, even our quality assurance testers,” she continues.

Personas enable product managers to communicate research insights internally and align on who the target user is with cross-functional team members. Having that understanding motivates everyone involved to solve core problems for the persona, Dibble says. It can also “help them imagine new solutions that make sense for your target user and support them in making decisions. When someone proposes a new idea, you can evaluate that idea in terms of the persona.”

They’re a key piece of storytelling as well. “Personas are great within your organization to tell stories about how you envision your target user using the product,” Dibble says, “and how this product solution will make their life better.”

How to Partner with Designers on Creating Personas

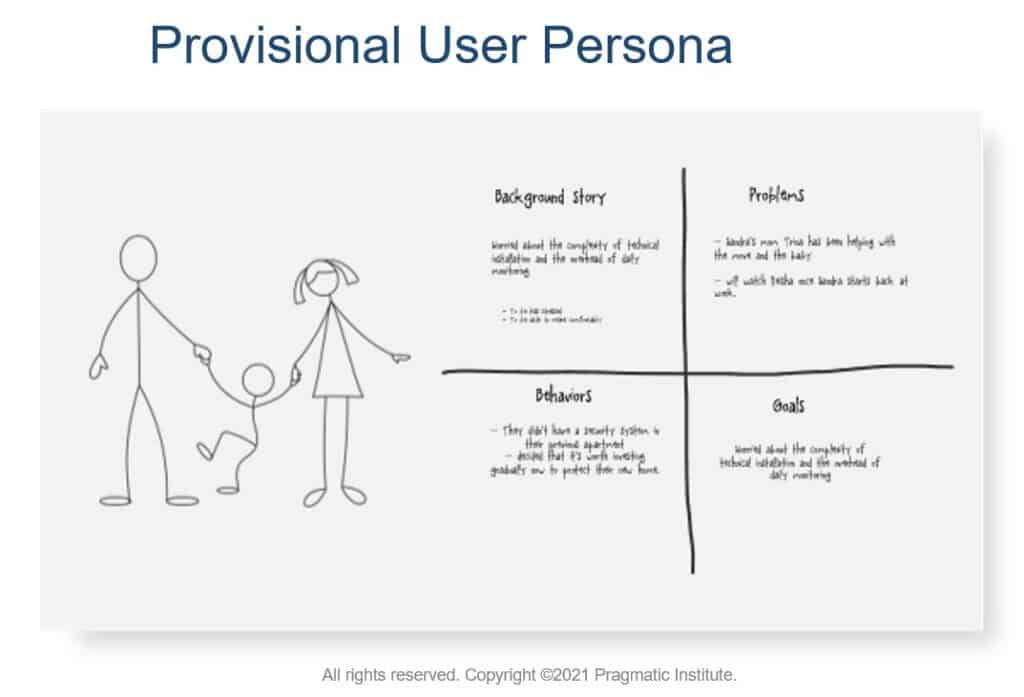

Whether you’re sketching out a provisional user persona based on what you know of the market thus far or crafting a fully refined user persona with your designers, it should be based on research. If possible, bring designers along in research to get a different perspective and build trust.

You can use what you know already and the interactions you’ve had with users to create a hypothesis about a target user to validate. “This is something you can do in a workshop, and it’s a great starting point. You can use a provisional persona (or “proto-persona”) as a way to direct your energies. It also can help you decide where the gaps are in your knowledge and what questions you want to ask as you go out to do user research or NIHITO [“Nothing Important Happens In The Office”] research to understand more about these people,” Dibble says.

Do qualitative research to figure out what influences users’ behavior and what their goals are, Dibble advises. Make a plan ahead of time knowing you want to capture goals, problems, etc. That will affect the questions you ask. The user persona represents your understanding of a target user, and the more you know about your user over time, the further the persona will evolve.

Amy reminds attendees that these differ from buyer personas: “the people who put on the buyer hat, the ones making the purchasing decision. They care about price, risk, and return on investment.”

Problems vs. Goals

While product managers focus on market problems, designers tend to look at goals the users are trying to achieve. For example, a salesperson’s goal is to meet their sales target, and SalesForce supports that goal by eliminating friction in pursuing and closing deals and allowing them to be more effective overall.

Dibble says, “The nice thing is that goals and problems are really mirror images of each other. If you have a problem it’s probably because it’s something that’s a roadblock for your greater goal that you’re trying to achieve.”

“I think one cannot survive without the other,” Graham agrees. “They have to co-exist.”

In your NIHITO research, when you uncover a problem, ask why it’s a problem and what that stands in the way of ― a technique for gathering those higher-level goals to bring back to your team.

Reframing Problems to Spark Innovative Ideas

Ideation leverages the brainpower and perspectives of everyone on your team to come up with new ideas. Make sure to prime them with that outside understanding first: who are we solving for, what are their problems, how are they solving them today, and what’s broken?

Cross-functional ideation helps the team:

- Establish an outside-in focus

- Collaborate more effectively on ideas

- Shows everyone as responsible for defining the problem

- Think in new ways

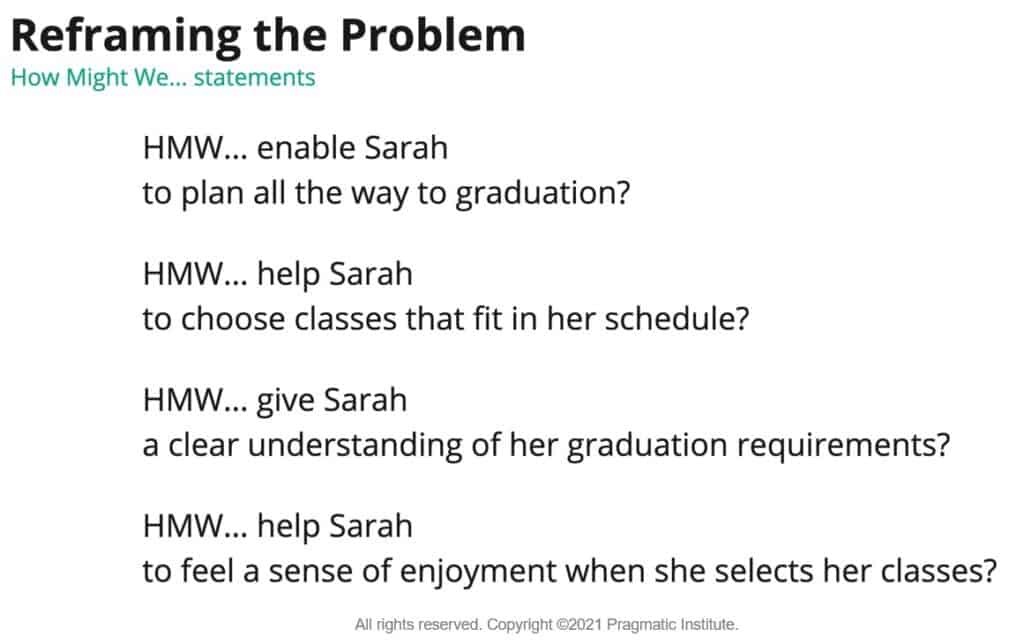

“How Might We” statements are just one tool designers use in ideation. These statements reframe the problem as an opportunity that allows the team to open up more possibilities for the persona and generate lots of potential ideas that could figure into the solution.

Take an example persona and problem from our Build course.

“This technique allows you to get in that creative space and that’s critical,” Graham says. The more empathy you can build in the user, the better product you can bring to market.

Graham and Dibble believe building a stronger partnership between product managers and designers will not just improve the product experience that’s delivered to the market, it will lead to fewer revision cycles, better visualization of the concept you’re seeking buy-in on, and a greater chance of internal approval on product decisions.

Author

-

The Pragmatic Editorial Team comprises a diverse team of writers, researchers, and subject matter experts. We are trained to share Pragmatic Institute’s insights and useful information to guide product, data, and design professionals on their career development journeys. Pragmatic Institute is the global leader in Product, Data, and Design training and certification programs for working professionals. Since 1993, we’ve issued over 250,000 product management and product marketing certifications to professionals at companies around the globe. For questions or inquiries, please contact [email protected].

View all posts