Imagine you are asked to develop a service that will be included in an unreleased Apple product. You will be one of the first people to get your hands on it and develop new use cases. You’re full of anticipation until you realize it’s an impossible paradox: you need to design an innovative service for this Apple product, but Apple won’t give you access to the device, design system or software development kit. You need to find another way, but can you?

This was a real-life situation for the Jaguar Land Rover product team. We were collaborating with Apple ahead of the release of the Apple Watch. The Apple Watch would launch with an app that, for the first time, would allow users to remotely operate their car. It was a vision from superhero comics that could finally be realized.

It was a dream product: we loved cars, loved Apple and loved new tech. Everyone knew developing a design language and system that held the same cues and craft as sporty Jaguars and rugged Range Rovers within Watch OS was a big challenge—not just intellectually and aesthetically but culturally. We needed to help overcome deep assumptions within the company, that digital design couldn’t achieve the same levels of quality as physical car design and styling.

Therefore, we were very intentional in methodology and collaboration to understand and integrate with the existing design systems, but also the technical systems. Synching up multi-modal communications between watches, phones, satellites, servers and everything in between is complicated. But we had the right people, capabilities and resources.

We never imagined we wouldn’t have access to the product we were co-launching. Even the product evangelists inside Apple had yet to get their hands on it. We might have stopped there. You’ve seen it: when the rationalization of why it’s impossible is paired with cynicism and blame. Eventually, an executive review puts a nail in the project and it’s swept under the rug. The project exists only as a form of corporate mythology whispered in hallways, showing that innovation just can’t be done here.

Psychological Safety: A Key Ingredient for Innovation

We didn’t quit. A team’s strength lies in its ability to flex under pressure. High-performing teams have psychological safety, meaning team members can share perspectives without fear of judgment and persecution.

What does psychological safety look like in practice? Psychological safety is the exchange or alliance between people—made up of the ideas between us and the responses within us. It is equally what is said and how it’s interpreted.

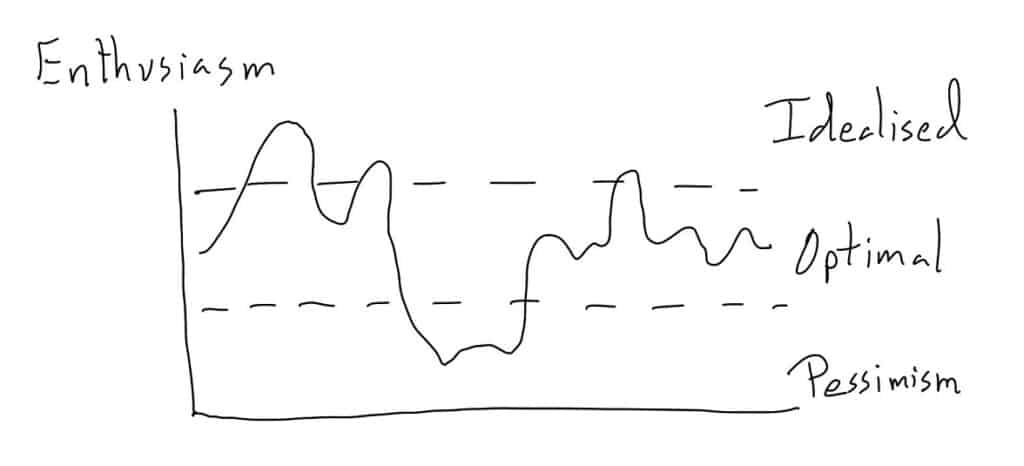

Innovation means high risk, high reward and high emotions. Great teams work through the highs and lows to hold balanced positions of performance.

In high-pressure situations, your frustration might come through; you might even lash out. Or, you might perceive something said in an even or friendly tone as an attack or attempt at manipulation. It’s easy to experience these dynamics but hard to develop the emotional regulation to withhold judgment and to elaborate on what you hear.

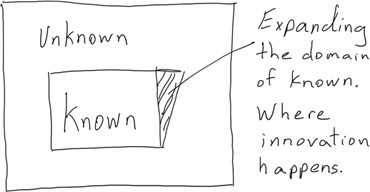

In my experience, this is especially true for innovation-tasked product teams. You are working outside the boundaries of known knowledge—trying to create a new product, service or process that doesn’t exist yet. Naturally, this creates anxiety. However, many professionals don’t think consciously about how they handle their own anxiety, let alone the shared anxiety in the team and the wider organization. Innovation means high risk, high reward and high emotions.

Great teams work through the highs and lows to hold balanced positions of performance. At times you need high energy and even magical thinking to unlock a situation and step forward. Other times you need realism and even cynical perspectives to stress test your solutions, hypotheses and assumptions. Those extremes, with psychological safety, help calibrate a return to the optimal zone of progress.

Building Resilience Through Uncertainty

In innovation programs, this cycle takes place in learning loops small and large. Just as elite athletes learn how to perform their best on different stages, so too can product professionals. It’s essential to have knowledge, capabilities and tools, but never take for granted the experience of working through the pressure and anxiety of uncertainty.

Repeat and resilient innovators are good at managing their own responses and withholding judgment, and the real goal is to make this a shared practice. Like learning a language, psychological safety is something most people understand intellectually but only learn by doing it badly at first. I encourage every design and product professional to see leadership as a capability and practice to develop alongside skills and process knowledge.

How to Know if You’re Safe

To create and maintain psychological safety, develop self-awareness of how external and internal situations affect your behaviors: namely, what you say and how you show up and act. Like an elite athlete, learn to identify what situations and emotions cause your worst performances. The more you eliminate these errors; the more you hit your mark at gametime.

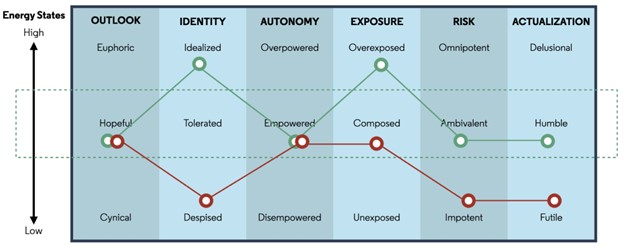

There are six drivers to an innovator’s mindset: outlook, identity, autonomy, exposure, risk and actualization. It’s okay if you end up in extreme positions, provided you are aware of it. Notice how and why you end up in cynical or idealized positions. Apply some self-empathy to understand why.

For the next month, every Friday, carve out 15 minutes to evaluate your current mindset. Keep notes of week-to-week variations. If you find an extreme position emerges for three or more weeks, that’s a signal to investigate what’s going on, because you’re stuck. If applicable, bring your findings into sessions with your professional coach or mental health professional.

Innovation is hard. It’s normal to experience extreme emotions. To maintain psychological safety you need to be mindful of how you interpret what is said and how your responses land with others. Intellectual conflict is necessary and healthy, provided it doesn’t carry a persecutory edge.

Shared Leadership and Accountability for Risk Taking

To return to the Jaguar Land Rover x Apple Watch story, we had a core team of a designer, developer and project manager with supporting business analysts and infrastructure architects. There was also interaction with brand teams, systems owners and safety-focused roles to ensure vehicles could operate safely anywhere in the world, secure from cyber incursion.

Anyone can serve as a leader at various times in a project. In the world of innovation, leadership is a shared role.

But still, we faced the fundamental blocker of no devices or SDK to work on. So, our iOS developer took a chance.

We did have high-resolution marketing videos from the previews provided by the Apple Evangelists. In front of the whole team and Jaguar Land Rover’s CTO, our developer said he could create his own emulator by deconstructing the interaction patterns and design system from the marketing videos.

This took accountability and confidence, driving change with the wider team to crack our roadblock. Leadership is an act, not a position. Anyone can serve as a leader at various times in a project. In the world of innovation, leadership is a shared role.

Innovation is about driving change through new ideas. This young developer wasn’t intimidated into silence by the legacy of this renowned company because our team was a judgment-free space. And as the senior authorities on the team, it was our responsibility to withhold our own anxieties, support him and own this decision together.

With time ticking down, we developed the emulator, designed versions of the service and tested it with users (who didn’t know it was for the Apple Watch). Just weeks before the official launch, we were given a device in a secure compound north of London where the service was rapidly put through its paces.

Only on one rainy day in January 2015 did we know for certain it worked in the real world. An ice-white Jaguar F-Type, fresh from Jaguar’s R&D center, prowled into London. Hovering around an Apple Watch, we booted up the app. A couple of swipes and taps later the roar of ignition echoed down the streets, washing out our cheers. We had done it. Weeks later, Tim Cook and Jonny Ives introduced our baby and theirs to the world.

Author

-

Brett Macfarlane, with 21 years of experience in leadership development, has left an indelible mark at renowned companies such as DDB Canada, Saatchi & Saatchi, and ustwo. A pivotal figure in the intersection of leadership and innovation, Brett's influence extends to his roles at Goss and D&AD. For questions or inquiries, please contact [email protected].

View all posts