8-minute read

In the 1980s, Intel rescued itself from a major sales decline by introducing growth strategies that supported OKRs. Learn how they implemented those strategies to exceed sales goals.

Intel’s Operation Crush was designed to combat a sales slump driven by a customer exodus to a new market competitor, Motorola. Former CEO Andy Grove introduced 3 ambitious strategies that enabled Intel to turn its sales around and remain a resilient and respected company.

Keep reading to learn more, or use the links below to jump to the section that most interests you:

- What is Operation Crush

- Intel’s Strategies for Growth

- Strategy 1: Implement an OKR Framework

- Strategy 2: Change Positioning and Messaging

- Strategy 3: Align Campaign Blueprint with Buyer’s Journey

In his New York Times bestseller, Measure What Matters: How Google, Bono and the Gates Foundation Rock the World with OKRs, legendary tech investor John Doerr featured the story of Intel escaping a near-death situation in the early 1980s.

Already rich in details thanks to Doerr’s professional background (he worked at Intel from 1975 to 1980), the story is further informed by Bill Davidow, then-VP of Intel’s microcomputer systems division. Davidow had a first-row seat during the crisis: Former Intel CEO Andy Grove chose him to lead the operation that would get Intel out of its slump and pave the way for its explosive growth as it went on to secure deals with multiple large clients, including IBM.

Though Davidow had already dedicated an entire chapter to this story in his 1986 book, Marketing High Technology, Doerr shared new, behind-the-scenes information that is of significant interest to tech innovators looking to thrive in today’s complex business world.

Intel vs. Motorola: Operation Crush

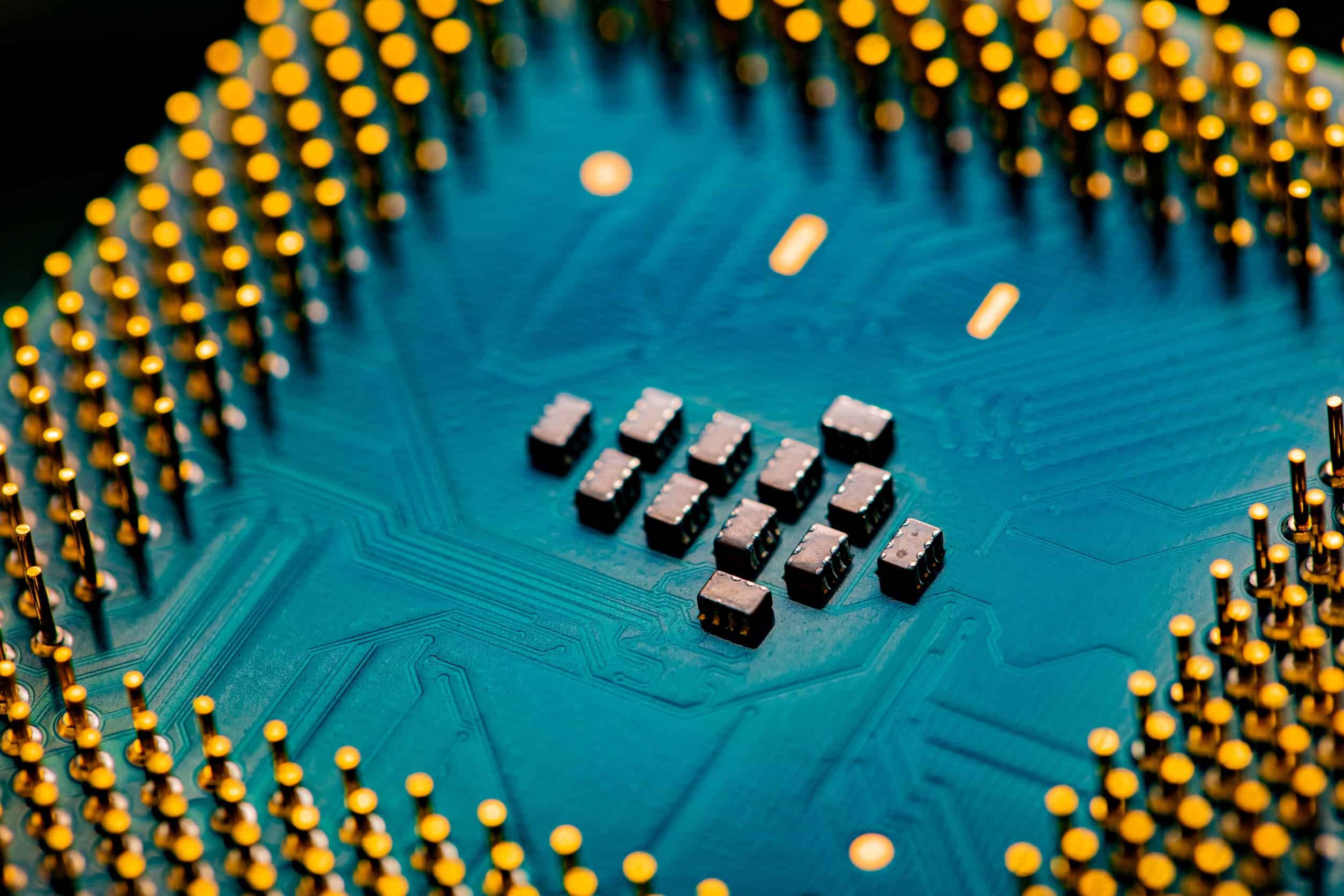

Intel’s 8086 16-bit microprocessor chip was introduced in 1978 and, according to Davidow, “quickly gained the top position in the market.” The chip captured the lead from older, less capable products that Texas Instruments and National Semiconductor supplied. However, it took two years to achieve wide use, and during this time, Motorola produced a competing product—the 68000—that was faster and easier to program. Clients noticed the difference and were eager to switch from Intel to Motorola.

Motorola was much bigger than Intel and had more than enough resources to push Intel back and grab the lion’s share of the market. Intel was in troubled waters. According to Davidow, several of Intel’s multimillion-dollar businesses depended on the success of the 8086. If it failed to secure its market share, the microprocessor division was at risk, and so was Intel as a whole. This fight-for-survival situation led to the creation of a special operation at Intel: Operation Crush.

Unwilling to settle for incremental gains, Intel’s management team decided to set an incredibly high goal: 2,000 design wins over the following year. This correlated to one new sale every month for every salesperson.

The sales team was dumbfounded.

Doerr recalled the reaction to the news: “Management was asking our field reps to triple their numbers for a chip so unpopular that longtime customers were hanging up on them. The salesforce was beaten down and defeated, and now it stared up at Mount Everest.”

Intel’s Growth Strategies

Little did he expect, though, that by the end of the year, Intel would surpass this goal, bringing in 2,300 design wins and recapturing 85% of the 16-bit microprocessor market. And all of this would be achieved without creating—not even modifying—a single product.

At its core, Operation Crush was a massive relaunch campaign of Intel’s existing product line. A thoughtful read of Doerr’s and Davidow’s books reveals that the campaign’s success was built on three fundamental strategies. Each strategy promises as much to present-day tech innovators looking to bring new products to market as it did to Intel in the 1980s—and potentially even more, considering today’s increasingly competitive market.

Strategy 1: Implement an OKR Framework

“As my dad used to say, no one becomes an astronaut by accident.”

–Keith Ferrazzi, author and entrepreneur

What are your top-level goals? Have you broken them down into smaller, measurable pieces with a fixed deadline? Those are the central questions Doerr asks in Measure What Matters. He has evangelized objectives and key results (OKRs) for years—a framework for defining and tracking objectives. From startup founders to CEOs of large corporations, many have been inspired to adopt the methodology. Today, the list of OKR believers includes Amazon, Google, Juniper Networks, VMware and more.

An OKR framework has four superpowers, according to Doerr

- Focus and commit to priorities

- Align and connect for teamwork

- Track for accountability

- Stretch for amazing (doing more than we thought possible)

Although OKRs may seem simple, their implementation comes with some risk. To this end, Doerr provides useful guidelines and examples to help management teams implement the framework.

Both Doerr and Davidow are adamant that Operation Crush would have failed without OKRs; they were the secret sauce that allowed Intel, then a billion-dollar company, to get thousands of employees to change course and work in an entirely new direction in (almost) perfect synchronicity—all in a two-week timeframe. “Intel Corporate Objective” is an example of Operation Crush’s corporate OKR for the second quarter of 1980, as provided in Doerr’s book.

In five short, declarative sentences, Intel stated its top-level objective and called out core tasks for four major departments, incorporating deadlines and measurable targets where appropriate. Department managers had no escape from Operation Crush’s OKRs.

- Develop and publish five benchmarks showing superior 8086 family performance (Applications)

- Repackage the entire 8086 family of products (Marketing)

- Get the 8MHz part into production (Engineering, Manufacturing)

- Sample the arithmetic coprocessor no later than June 15 (Engineering)

In terms of Doerr’s aforementioned list of superpowers, it’s easy to see how the OKR framework brought focus, alignment and accountability to the team. In the end, OKRs gave Intel’s cargo ship the agility of a laser sailboat.

Strategy 2: Change Positioning and Messaging

“I would rather be different than better.”

–Bill Davidow

Examining Intel’s OKR list, we notice that the second key result, “repackage the entire 8086 family of products,” is the only one without a deadline or measurable goal. It’s also a bit of a mystery. What exactly does it mean to repackage? Doerr and Davidow both provided ample explanation. In fact, if there was one key result they insisted on as they described Operation Crush, it was this.

Intel knew that Motorola’s 68000 was a better device. The company also knew it would lose if it kept the discussions happening at the microprocessor level. This forced Intel’s management team to spend significant time and resources to find a way to change the 8086 product’s position and message—to repackage it.

Davidow recalled hiring Silicon Valley’s top marketing consultant at the time to help drive this process. Out of intense strategic sessions came a realization: While Intel looked bad from a pure microprocessor standpoint, it had several advantages over Motorola from a system-level standpoint, including a broad product family, better system-level performance, and a better-trained technical salesforce. The net result for customers, the team asserted, was a reduced risk of integration problems, faster time to market, and a more efficient engineering team. The team was on solid ground to create a new narrative.

Intel not only changed its positioning and messaging, but it also changed to whom it promoted its new message—the company stopped selling to programmers and started selling to CEOs. This was essential to Operation Crush’s success, as most programmers had little interest in the new features and benefits Intel was about to offer.

What mattered then continues to matter today: Repositioning a product for a higher-level audience is a powerful, strategic move for technology innovators to capture new growth. In fact, redefining the industry buyer group is one of the six paths to growth in another New York Times bestseller, Blue Ocean Shift by W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne.

One caveat to remember is that successful repositioning requires properly segmenting the market. “In actual practice, a marketing department that talks to enough customers will gather sufficient data to define enough markets to guarantee confusion and paralyze any management team,” Davidow wrote. The solution, he insisted, is to “identify the dominant characteristics in a customer population.”

Clearly establishing Intel’s differentiator, this breakthrough system-level positioning formed the basis of a new message and value proposition that the company relentlessly marketed over the following months. “We had been playing to competitors’ strengths, and it was time to start selling our own,” Davidow wrote. This was the turning point for the Intel team, and they never looked back.

Strategy 3: Align Campaign Blueprint with Buyer’s Journey

“People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill; they want a quarter-inch hole.”

–Theodore Levitt

Equipped with a new value proposition, Intel’s management team organized the company to deliver the message. Whereas the repositioning and messaging effort required a lot of thinking and brain power, this last strategy is about taking massive action. A campaign blueprint is the guiding map to ensure all actions are aligned with one another.

This step is thoroughly described in Davidow’s book, wherein he strongly advocates for a systematic approach to marketing campaigns. This starkly contrasts the collection of disjointed activities he witnessed at other high-tech companies. Rather than random acts of marketing, Davidow favors an approach that relies on systems that are subject to quality control.

Inherent to this approach is the need to break down the path leading to a sale. The result, often referred to as the “buyer’s journey,” describes the key learning elements clients need to evolve in their journey from suspects to prospects to qualified prospects and, finally, to clients. For most technology innovators, the buyer’s journey can be broken into three main stages: awareness, consideration and decision. Rather than trying to take a shortcut and go straight to the sale, “Operation Crush Campaign Blueprint” shows how the company aligned with each stage of the buyer’s journey.

“The sheer complexity of technology products is often a trap,” according to Davidow. “Time and again, a high-tech company will try to tell its customers everything about its complicated product in a single promotion. The resulting copy is impenetrable, the headlines are long and arcane, and the graphics are incomprehensible. It is always easier to tell a lot about a product than to tell just a little. But simplicity is the key.”

Even though they were proud of their new product and eager to inform the market, Intel knew that most customers would not care about their new datasheets and demos—at first. To get there, Intel had to warm them up.

To achieve this, Intel first directed prospective customers to their awareness-level content. The goal was to make them realize they had a problem and recommend seminars to learn about Intel’s top-level solution. After the seminar, prospects went through a qualification process and then were offered the opportunity to attend a users’ forum during which more in-depth information was provided. Only then were they exposed to demonstrations and product-focused technical information.

Like a trail of breadcrumbs, this alignment of content to the buying process allowed Intel to gradually build trust and guide buyers on their journey from prospect to client.

Motorola’s Billion-Dollar Mistake

As with all principles, these strategies aren’t applicable only to major corporations and product relaunches. Tech companies of all sizes regularly apply these principles to launch new products, whether they’re medical devices, industrial systems, telecommunications equipment, or consumer electronics. Regardless of the industry or product, the principles remain the same—it’s their implementation that varies.

In the case of Intel versus Motorola, the result was far from inevitable. Motorola could have used these same strategies to its own advantage. “(Motorola) had the opportunity to consolidate its victory, yet instead, it fell into the trap of confronting our strengths head-on,” Davidow explained. “(The company) could have been different, but it chose to be the same.”

Rather than defending against Intel’s strategy by calling it out as an act of desperation, Motorola legitimized Intel’s efforts by going toe-to-toe—but with an inferior imitation.

“Had Motorola chosen to remain aloof from our challenge, I think Intel would have been in deep trouble,” Davidow wrote. And this is a great reminder that if you don’t have a strategy, you’re probably part of someone else’s.

Authors

-

Stephanie Labrecque, a thought leader in technology product management with 25 years of experience, has left a lasting impact at organizations such as Nortel Networks, Gentec-ceo, and Pragmatic Institute. Her expertise extends to addressing the unique issues and challenges inherent in creating technology-powered products, services, and experiences. Associated with Inspira Strategies, Stephanie remains dedicated to advancing the product management field. For questions or inquiries, please contact [email protected].

View all posts -

Etienne Fiset, MBA, EE, brings 21 years of expertise to the realm of marketing high-technology products. His journey includes impactful roles at Infineon Technologies and Gentec Inc., where he excelled in guiding technology innovators. Etienne is recognized as a proficient strategist in companies such as Nutaq, Pragmatic Institute, and Novo123. For any inquiries or questions, please contact [email protected].

View all posts