Pragmatic Institute Framework

The Pragmatic Framework offers an actionable approach to building products that customers want. It provides a clear and simple path from great ideas to great products.

250,000+

Total Alumni

40,000+

Active Alumni members

using the community

using the community

8,000+

Active companies using the

Pragmatic Framework

Pragmatic Framework

Get your copy of The Pragmatic Framework

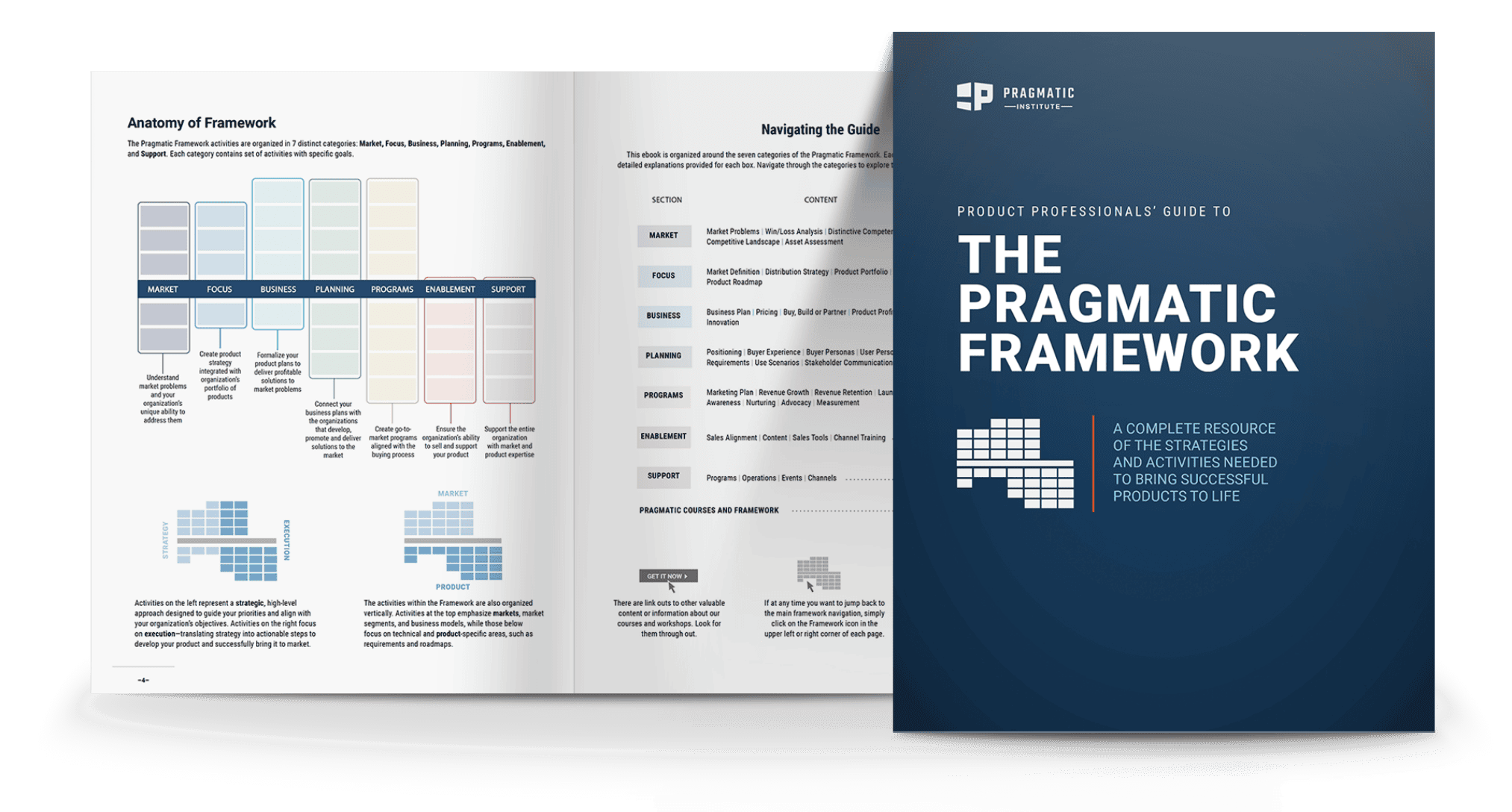

Pragmatic Framework, once popularly called the Pragmatic Marketing Framework, consists of 37 boxes arranged in 7 categories. Each box represents key activities and responsibilities across the entire product lifecycle, helping teams understand what to focus on at each stage to create successful, market-driven products. Together, they provide a comprehensive roadmap that aligns teams with market needs and business goals.

By following the Framework, companies can ensure their products are strategically positioned for success from concept to launch.

Explore The Pragmatic Framework

Click the boxes to explore eight essential concepts from the Pragmatic Framework. For a complete breakdown of all framework components, download the eBook.

Download The Pragmatic Framework

Download our ebook for a detailed explanation of some of the key concepts of the Framework.